Islington Gazette, 23rd February 2024

Exclusive by Charles Thomson, Investigations Reporter

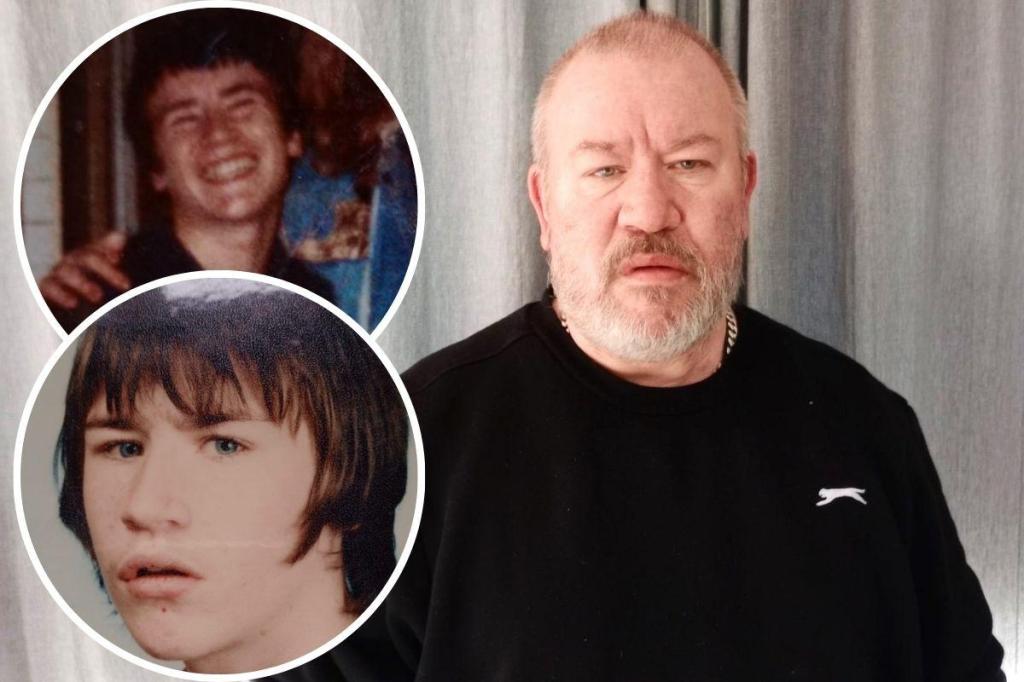

A man calling for support after he was left addicted to drugs after years of abuse in children’s homes found his care records had been lost.

Max – not his real name – says he was placed in two Islington Council children’s homes in the 1990s, where children and staff used drugs and he lived in fear of sexual assault.

But when he applied for his care records to support his bid for a £10,000 payout, the council could not find them.

“This is potentially very serious,” said Dr Liz Davies, of the Islington Survivors Network (ISN).

Councils are supposed to keep the records of looked after children for 75 years.

Dr Davies said she had referred several people with missing or incomplete files to a lawyer to see whether a legal action could be brought.

Islington Council would not comment on Max’s case, but said applicants to the support scheme did not necessarily need their care records.

However, Dr Davies said other applicants whose records were missing or incomplete had been turned down.

‘Children smoked crack’

Max said he was taken into care in 1993 and placed in the former Northampton Park children’s home, near Canonbury station.

He said some staff there openly smoked cannabis and permitted children in their care to smoke cigarettes and other substances.

He was given hashish, he alleged, and witnessed other children using crack cocaine.

He was neglected, he claimed, with nobody noticing conditions he was later diagnosed with disorders like dyslexia and ADHD, which impacted his education. He left school with no qualifications.

The home was also rife with rumours of sexual abuse, he said.

“Other kids told me something bad was happening in the home,” said Max. “They said to keep away from certain people.”

At night, he claims, he would put furniture against his door and was frightened to go to sleep.

Heroin addiction

Max said he was later moved to another children’s home and got no help finding accommodation after turning 18.

His adulthood has been marred by heroin addition, which sabotaged his career in IT, and failed relationships. At one point, he lived in a hostel.

Only now he is clean and sober has he joined the dots between his childhood trauma and his destructive drug use.

“I was trying to forget,” he said.

He now has constant pain in the left side of his body, which he believes is linked to his past heroin use.

He also has depression – not helped, he said, by living in a rented studio flat so dilapidated that he can’t use his own bathroom. He has to visit a relative daily to use theirs.

He is on the council’s bidding list for a one-bedroom flat, but several thousand places from the top.

Missing file

After admitting and apologising for decades of abuse in its former children’s homes, Islington Council set up the Support Payment Scheme, offering £10,000 to survivors.

Dr Davies helps survivors obtain their care records and file applications.

The Arrangements for Placement of Children Regulations 1991 say case files should be kept until the looked-after child’s 75th birthday – but Max’s cannot be found.

“It’s important to note that we do not require a care file to be supplied as part of an application for the support payment scheme,” a council spokesperson said.

“We don’t want potential applicants to be dissuaded from applying.”

But Dr Davies said some previous applicants have been rejected under similar circumstances.

In January, the Gazette reported on Zara, also not her real name, who was rejected after receiving an incomplete care file.

Like Zara, Dr Davies said Max’s memories – the names of staff and children at Northampton Park, and his descriptions of what happened there – are corroborated by other survivors.

But Zara was still turned down and told to apply to an appeal panel if she wanted to pursue payment.

The same happened to another applicant, Tony Darke, even with a care file.

Max’s Dream

If Max received the £10,000, he said, he would first book some private therapy – something he started once before but could not really afford.

“If you want it on the NHS you have to wait forever and you might die before you ever get treated,” he said.

He says he would then invest in some IT training to try to get his career back on track.

“I think the main thing I need is to find a nine-to-five job,” he said.

“The payment would definitely improve some things in my life. It’s not something that would go to waste.”

Once he is back on his feet, he said, he would like to help other recovering addicts get their lives back on track.

The payment scheme is open to applications until May. Visit www.islingtonsupportpayment.co.uk.

Islington Survivors Network can be reached at 0300 302 0930 or islingtonsn@gmail.com.