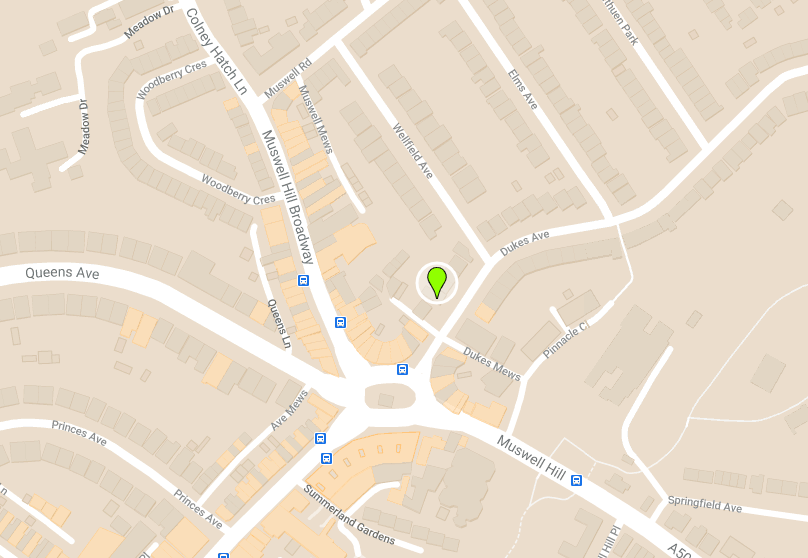

Address: 1 Dukes Avenue, Muswell Hill, London N10 2PS

Open: 1973 – 1998

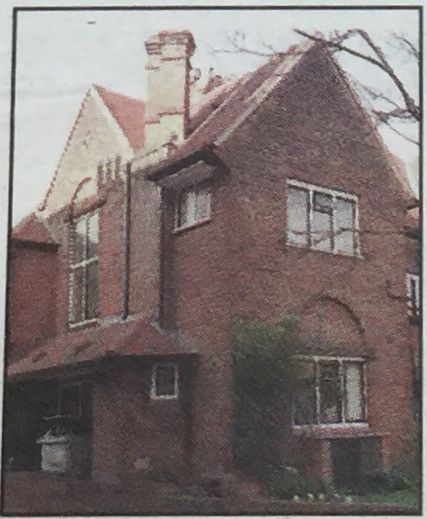

Colgrain is a children and young persons establishment accommodating 6 young people situated in Haringey on the edge of Muswell HIll Broadway. It is a converted 5 bedroom bay windowed detached Edwardian house, brick built with a terracotta tiled gabled roof. There is a small garden to the front with rose trees and shrubs and a larger garden with a paved area and small lawn with a pond to the rear. A garage and garden shed are situated at the top of the garden. It provides longer term care. An Islington Statement of Purpose said it aimed to provide a caring environment where the emotional, cultural and physical needs of young people can be met. The unit worked with residents and their families to prepare them for fostering, with young people to enable their return to their families and also to prepare young people for independence. The unit worked with young people with a range of difficulties, including poor school attendance, behavioural problems, experience of physical, sexual and emotional abuse, poor cultural identity, young people who have had allegations of sexual assault made against them, refugees, young offenders and young people following foster placement breakdown. (Betts Inspection Report 25.9.92)

‘The man in charge got me so angry I smashed all the windows and gave him a big ‘box in the head’. .. I was sent to Detention Centre. When I returned to Colgrain I was told I was not welcome there and that my bed was taken. I couldn’t understand what was going on so I left Colgrain and where was I supposed to live? I took a bus to Archway to see my social worker. This was no help as social services was on strike. I was angry and confused. How could I be homeless? I had always had a home. Islington Council looked after me. They’re my so called parents.’ (Bobby Martin – 1978)

‘These children are in their third year at Colgrain and 46 highly disturbed children have passed through the home in that time. Children are increasingly unsettled at the number of children seen coming and going in Colgrain.’ Staff from Colgrain – file record 80s.

‘The Superintendent did Pin Down – he’d hold your arms up and put his knee in your back on the floor.’ ISN Survivor

‘I asked for tomato sauce – the worker said ‘What did you say?’ He said I didn’t say ‘thankyou’ and so I got beaten.’ ISN Survivor

‘One young boy was pinned down – he went beserk.’ 2 ISN Survivors who witnessed this.

‘Just before I went to Colgrain there had been an incident (July 84). It was empty as early in 1984 they had got rid of all the kids. One girl was sent to Middlesex Lodge.’ ISN Survivor

Number of ISN survivors that lived at Colgrain children’s home. 13: 6 men and 7 women

Numbers of children named by ISN survivors as living at Colgrain children’s home: 59: 36 boys and 23 girls

Residential staff named by survivors as working at Colgrain children’s home: 38: 17 men and 21 women

Numbers of children named in council documents as living at Colgrain children’s home:

In 1975 a survivor’s file states that 3 children in Colgrain were ‘ autistic’ – yet it was not designated for the care of children with disability.

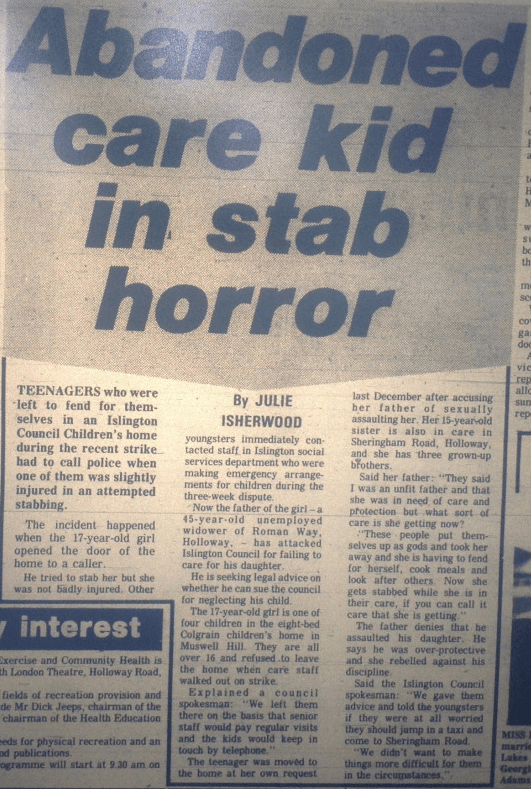

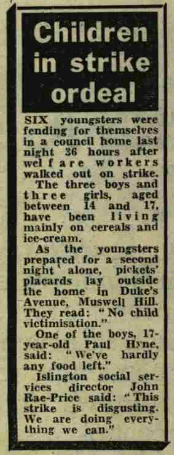

In 1981 the Daily Mirror reported on the impact of a strike on children in Colgrain. The article refers to 3 boys and 3 girls between the ages of 14 and 17 years.

In 1992 savings were being made by Colgrain, 29 Highbury New Park and Grosvenor having 27 places as Grosvenor was no longer having 3 bedded units.

In 1992, the Betts Inspection report described 6 young people in residence, their length if stay being 1-3 years and their ages being between 14 – 17 years. 4 of the young people had English as a second language.

In 1999 there were 6 long term placements for young people age 14-18 years (Islington Gazette 19.3.99)

‘Some children came from Dixton when it closed [1985].’ ISN Survivor 80s

Life at Colgrain children’s home

In the 90s this home was the subject of investigation following the Evening Standard allegations about sexual abuse by staff and financial irregularities. The regime at this home was brutal and many of the survivors speak of sexual and physical abuse by staff. It was a small long stay home outside Islington – the age range of children was mainly 13 – 17 yrs but there were some younger children. One member of staff took a number of children to his home regularly – he is now deceased- and they were exposed to abusive images (animations).

In 1993 the Betts Inspection report stated that full staffing consisted of a Superintendent and 2 Deputy Superintendents and 4 residential care officers. There was also an administrative worker, a part time handy person and a cleaner.

‘I was beaten mercilessly.’

‘I had bruises from a member of staff – I was told I bruised easily.’

‘In the first year I was at Colgrain I was sexually assaulted 3 times.’

‘There were drugs at Colgrain.’

‘My sister was moved and I didn’t know where she had gone. No-one told me.’

‘I was only 9 years old – Colgrain was beatings and 100% sexual abuse.’

‘I was kicked and dragged and locked in for hours – that was regular.’

‘We were deprived of food as a punishment.’

‘Two of us were put on the pill by Brook Rd Clinic at Manor Gardens – we were only 14.’

‘For terminations of pregnancy we had to wait because Islington wouldn’t pay for us to go to a private clinic.’

The BETTS Inspection Report 1992

The Inspection Reports covered 3 children’s homes, Colgrain, 80 Highbury New Park and Grosvenor Avenue.

Please read the account of the history of these reports on the webpage for 80 Highbury New Park https://islingtonsurvivors.co.uk/80-highbury-new-park

The reports have only in 2025 come into the possession of ISN having been hidden from view since they were written and unavailable to ISN when we made FOI requests. There was publicity about the reports in 1993 (Evening Standard (1993) Child home inspector is demoted. 11.03.93) which exposed the fact that the report had not been made available, by the council, to the early 90s’s inquiries. Sarah Morgan QC in her Report, in 2018, referred to the Betts reports being discussed in the Case Review Sub Committee which she said had been unresponsive to these very serious allegations.

Staffing was inadequate

The report referred to concerns about staffing. The established staff should have been a Superintendent and 2 Deputies with 4 Residential Care Workers. But, ‘in effect staff consisted of an Acting Superintendent and 2 Residential Care Workers‘. This was following the suspension of one Deputy Superintendent and the maternity leave of the Superintendent and one RSW. Together with issues of sickness, the unit depended heavily on agency staff. ‘Agency cover was at a dangerous level‘ and often there were no Islington employees on duty. Agency staff often worked full time in other Boroughs and this was a second job. ‘The young people perceived themselves as being looked after by strangers’. Some shifts had no Superintendent or Deputy present.

There were, at the time of Inspection, no qualified members of staff at the unit. There were no trained first aiders or fire marshals. Only one had some training in child protection and no training profiles were available to the Inspection. There were no night waking staff but 2 staff slept in in case of emergencies which Betts considered appropriate for the size of this unit. Because of current staffing problems formal supervision was not taking place with all the staff concerned. Betts made recommendations to cease the over dependence on agency staff who he said should only be employed to cover short term emergencies. He said that a designated competent person should be responsible for the home on the premises and this role should not be delegated to an agency worker as had been the case.

The physical state of the building

Betts noted that rain leaked into one of the bedrooms where a basin on the floor was collecting water, a sleep in room and kitchen. (Jane Frawley, coordinator at ISN, worked a shift at Colgrain in 1991 and had also witnessed buckets in the playroom collecting the rain water). He also noticed problems with security and a lack of locks in bedrooms leading to young people being able to gain entry particularly at the front of the building. Betts described footprints on a windowsill used by young people as an entrance/ exit to the unit.

He commented on rooms without lampshades or curtains, torn wallpaper, unclean and soiled carpets, ceilings and walls stained from water penetration, a broken mirror, a broken door handle, a broken shower, a bathroom without a shower and with a broken lock and a soiled settee. He noted remnants of Christmas decorations from 1991 and a large room containing broken furniture which had no light.

Betts recommended all the rooms to be appropriately equipped with furniture as required by government guidance. He said that broken furniture should be removed and replaced. He was concerned about fire safety and stated that beds, bedding, curtains and furniture needed to be flame and smoke retardant. He acknowledged that sometimes furniture and rooms can become damaged by young people but that there should be an allowance in the budget for rectifying such damage. ‘It is not acceptable that young people should be daily reminded of a disturbed episode in their life that happened and has been dealt with months and even years previously’. Betts noted that 3 bedrooms were undersize and not in line with regulations.

He described a clean and well stocked kitchen with appropriate foods but that utensils and crockery required restocking. The dining room needed new floor covering and redecoration. He commended the staff on their care and attention to the kitchen and dining areas. The laundry area allowed young people to be responsible for their own laundry which was ‘distinctly normal’. There were also fully integrated fire precautions systems in place.

The views of the young people

The young people at a meeting with Betts said they wanted a TV and Video that worked properly. They had concerns about the security of their rooms and valuables some of which they left with friends for safe keeping. Some said their belongings had been damaged or stolen. They were not of an age to insure valuables and there had been no compensation to two young people – whose valuables were stolen 1 and 2 years ago.

A major issue was the use of Agency staff. One young person said ‘How would you feel if you went off to school in the morning came home and the doors were locked, someone who you’ve never seen before answers the door and says ‘ Who are you? He should be telling me who the hell he is not the other way round, I’ve lived her for 4 years’.

Staff said they had no funds for decoration and had begged some from local shops and decorated the lounge themselves.

Care practice issues

Betts recommended that the restriction of phone calls and visits to friends should cease as sanctions as they contradicted the Children Act (1989) regulations.

The young people could access a phone in the office and make a private call for 5 minutes each day and at this time staff needed to vacate the office which was not always possible. It was also not always possible for young people to receive phone calls. This was unacceptable.

There was no sign of a complaints and representation protocol but there, ‘were an abundance of complaints, many of which were justified and had been frustratingly absorbed within the unit’.

There was only sporadic evidence of child in care reviews on files (some had none and others were over a year old) and in some cases only the reception into care papers were available. There were few examples of written agreements and care plans. The Borough had protocols for care planning outlined in the Islington Children Act Handbook.

All the young people had individual personal care files enclosed in ring binders. The files were appropriately divided into sections covering education and monthly summaries and reviews/reception into care papers/ medical reports.

There was no evidence of a written procedure when a child went absent without authority. One young person was regularly absent for periods of weeks and days. Notification was made to the Neighbourhood Office and people who had parental responsibility, but only when appropriate to the young persons age and length of absence. There was an admissions and discharge book listing the movements of all the children and young people who had been in and out of the unit since 1973 when it opened. This recorded the date of admission, date of birth, placing social worker, responsible team, Neighbourhood Office, the young person’s home address, their gender, age and date of discharge. There were separate books for medicinal records, accidents records, the administration of medicines, fire inspections, valuables in the safe, staff rosters, sanctions and a daily log for each child. There was no book for visitors. There was a logbook for the name of every staff employed with a record of qualifications and experience but not for agency staff.

Betts recommended that the sanctions book must be found and replaced and that there should be a profile of each Agency worker provided by the Agency itself. He wrote that there must be written care agreements and plans for each child. He concluded, ‘There was little evidence of the Children Act having had any impact on the young people accommodated. This needs to be addressed through the implementation of the statutory recording procedures. This area will be reviewed at my next inspection‘.

There was not to be another Betts inspection as he was demoted from his post and not then allowed to work within children’s services. This was reported in the article below and was instructed by the Assistant Director of Social \services without any due process. Sadly these important reports lay silent for decades together with the views of the young people he had so carefully and thoroughly included.

‘Children abused by pimps in Islington’

Evening Standard, 1st August 1994

By Eileen Fairweather & Stewart Payne

PAEDOPHILES, pimps and drug pushers preyed upon young people in Islington children’s homes, a damning report states today. Child sex abusers were able openly to telephone and recruit from the borough’s homes, “luring” boys and girls with offers of drugs, alcohol and money from under the noses of those entrusted to care for them. Children absconded and regularly stayed away overnight. Pimps were able to leave messages and money. Staff often had no idea of the whereabouts of children.

Fears that they were being abused were not properly investigated and the report reveals astonishing naivety by those caring for difficult inner-city children. Quite simply, they were able to run rings around care workers.

The report graphically highlights the plight of a 13-year-old boy who absconded 90 times and was feared to be involved in a paedophile ring. Yet it took the council 30 months to investigate his case, including holding meetings which no one attended. In the end nothing was done because “the trail had gone cold”.

The official report, which Islington council tried to keep secret, accuses its social work management of shocking negligence and bungling incompetence. It goes to the very heart of an Evening Standard investigation into scandalous child care practices in the borough. Central to the newspaper allegations was the claim that children were victims of paedophiles. This is now confirmed. A series of earlier reports have already endorsed accusations of management incompetence, an unworkable organisation and a dogma-ridden administration.

This latest independent report is highly critical of the council, particularly senior management. It also censures local police for their failure to investigate pimps targeting children’s homes and area police chiefs are now considering whether to take internal disciplinary action.

And even when staff expressed concern there was little evidence of “senior management activity” in dealing with the matter, says the report by independent social services expert Emlyn Cassam. But, most damaging of all to the Labour-run council, is the appalling lack of senior management response to fears that network sex abusers were exploiting children in its own homes. Mr Cassam’s report concentrates on the handling of just one of the many abuse cases the Standard highlighted although it has many parallels. The boy, referred to as “A”, arrived in care at the age of 13 from a disturbed family life having been beaten by his mother.

He was always going to be a difficult child to cope with. For this reason alone, Islington should have used all its skills and resources in attempting to rebuild his shattered life. Instead, he was further abused. Throughout his time at an Islington children’s home “A” regularly absconded, he played truant from school, his criminal activity increased and he used alcohol and drugs.

He told an agency worker at the home that he was seeing a “big, fat Jamaican”, aged about 50, who gave him money. “He lured boys and girls with bribes of money and dope. After a while he lined up punters to go with them.” He named that man as “George”. He said he had not done anything with the man “yet”, was scared of him and afraid of being hurt rectally.

This conversation should have raised sufficient alarms to spur the council into action. It didn’t.

The worker acted correctly in reporting the conversation to a senior. Girls in care were also overheard talking about a man called “fat Alan”, who was known to give money for sexual favours and leave messages for boy “A”. The man was now making direct contact with children in other homes.

The local police child protection team were informed and meetings between the council and officers were held. It became clear that George and Alan were probably the same man. From then on the inquiry dragged, even though there were by now young people from three different homes possibly involved and apparently more than one pimp. The Cassam report states that both police and council failed to instigate an overall strategy to investigate the evidence. In fact, there appears to have been a naive willingness not to investigate because boy “A” claimed he had ceased contact with “Fat Alan”.

Yet concerns over the welfare of boy “A” remained. He continued to abscond. A report at the time stated: “Roughly speaking he has been missing 90 times. He goes to see a man…who we think is a paedophile”.

THE Cassam report states that this was the first time that the plight of “A” he been reported to the local neighbourhood office of Islington social services. Not true. One of the Evening Standard’s informants Neville Mighty, a children’s home deputy, had reported the case of “A” a full year before to the then head of children’s homes Lyn Cusack. The council had no excuse for not acting at a senior level to investigate the case of “A”. It didn’t. Instead Neville Mighty, who had reported a pimp sleeping with a girl in care and 10 runaways from other Islington homes being introduced to child sex rings, was sacked. He claims this was in a bid to silence him.

Cusack, married to a senior police officer formerly in charge of Islington child protection officers, resigned from the council last November in the wake of the Standard allegations. Throughout 1992, meetings were held to review the case of boy “A” and in August the council’s child protection co-ordinator Sara Noakes remarked that she would consider a joint meeting with police “when enough information has been gathered”.

Finally police promised surveillance of suspects’ addresses but nothing happened. Pointedly Mr Cassam states in his report: “For six months staff in the neighbourhood services department believed that the police were pursuing enquires. They were not”. He adds that social services failure to chase up police “shows a surprising lack of urgency”. Instead memos were flying around requesting “a sharing of information” and a meeting was set up at which “nobody turned up or sent apologies – including the police”.

Meanwhile, pimps were still contacting children in care and one girl admitted she had “been with older men for money”. During this time a children’s home closed after a “riot” involving boy “A”. The disturbance was said to be over drugs and money.

Eventually, in February this year, 30 months after children’s homes head Lyn Cusack was first alerted to the fears over boy “A” and others, her deputy John Goldup, reported: “It appears that a man acting in an organised way, and possibly with others, ‘targeted’ children from at least one home”. Boy “A”, the victim of Islington’s indifference, is now in custody.

Mr Cassam concludes that children’s homes were “unable to control or modify” children’s behaviour; case files showed that senior staff didn’t have “any grip on events”; and “there was no evidence of senior management activity in dealing with the allegations of organised abuse”. Mr Cassam praised new child protection procedures set up by Islington follow the Standard investigation and subsequent independent reports.

An Islington council spokesman denied that the Cassam report had been withheld to avoid bad publicity, stressing the decision had been made on grounds of confidentiality. “We acknowledge that things have gone wrong and are determined that, over time, we will build one of the best social services departments in the capital”.

A Metropolitan Police spokeswoman said that senior officers had received a copy of the Cassam report and noted its findings. As a result new recommendations are to be made to child protection teams. There are no plans to discipline officers.

Ivy Gayle was a very brave residential social worker in Islington who blew the whistle on child abuse. She worked in Colgrain children’s home and also at 114 Grosvenor Avenue and was sacked after raising concerns.

Holidays

Children from Colgrain children’s home were taken to Spain and Wales in the 80s and survivors describe managers leaving them to look after themselves with one accident with the council van and another where a child was injured assisted to hospital by her peers. Survivors of these holidays describe neglect and some also speak of abuse. More information on the Holidays page.

Industrial Action