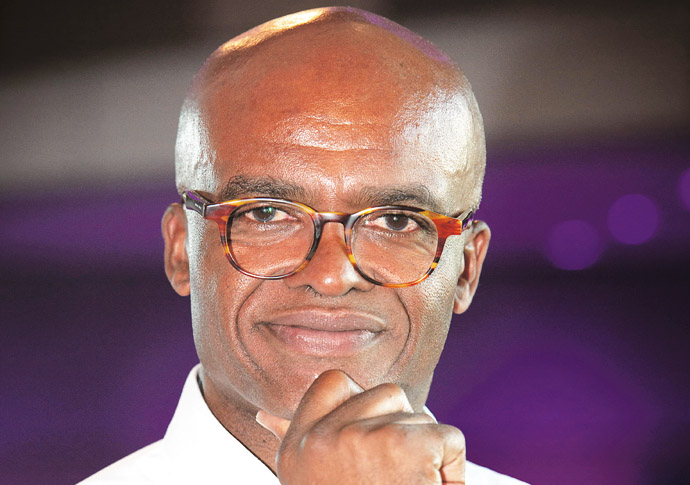

Interview with Dr Liz Davies who was made an OBE in the New Year Honours 21.1.26 Professional Social Work Magazine

Protecting children from abuse has been Liz Davies’ life’s work. In the 90s, as a social worker in Islington, she investigated and exposed abuse at 41 children’s homes.

She has been disbelieved, discredited and even received death threats. But she kept going, fuelled by her social work values.

In 2017, her dogged determination was vindicated with an apology from the London borough’s then leader Richard Watts to survivors, and herself, for “the council’s failure historically”.

A support payment scheme was set up offering £10,000 to all survivors of which more than 450 have benefited.

Though the scheme has now closed, The Islington Survivors Network founded by Liz with survivors in 2014 continues to investigate on behalf of and support survivors. Some 800 people have come forward providing statements of abuse in the homes dating back to the 60s.

“The survivors’ information about abusers is priceless in terms of protecting children now,” says Liz. “The reasons why they made those statements was to protect children now. It wasn’t for the money.”

Since the 90s public awareness of child abuse has grown. There has been the uncovering of horrific abuse by disgraced television personality Jimmy Savile. The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. Sex trafficking by Jeffrey Epstein and allegations of other powerful men in his network of abusers, including Andrew Mountbatten Windsor. The grooming gangs scandal.

Despite this, Liz believes cultures of disbelief still exist.

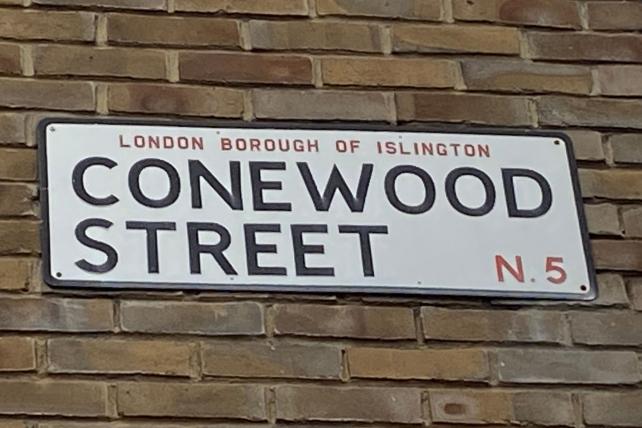

“I raised the alarm in the 90s, as a senior Islington social worker, about an organised network of child sexual exploitation that I witnessed between 1986 and 92.

“I have since spent 35 years seeking justice and healing for the survivors – but even now the struggle continues and the battles are ongoing.”

Liz says she was met with “numerous obstacles” when she uncovered evidence of children being “networked to child sex abusers” in Islington.

“In the 2020s, survivors told me that 50 children at a time were in this flat which ran as a ‘peep’ show for the posh cars that pulled up at the window.

“Survivors also told me that staff took them from children’s homes into forests at night and abandoned them there, leaving them to find their way back. They told me that men would try and drag them into their cars and that the children would hang onto each other to try and avoid separation.

“There is still no investigation of what I consider to have been many examples of child trafficking. Similarly I have on record that Islington children and Jersey children were swopped between abusive children’s homes under the guise of ‘holidays’.

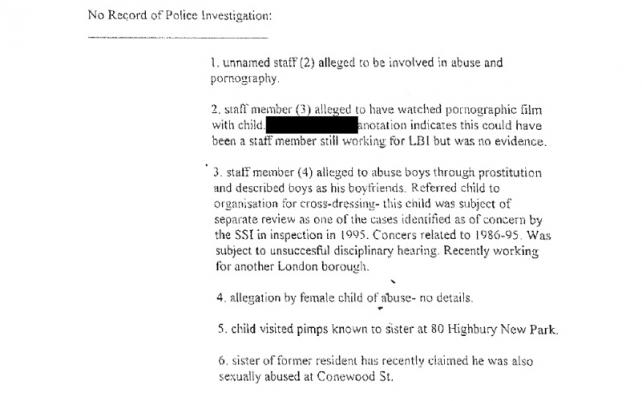

“I have collated the names of 80 known and alleged abusers, mainly residential workers and visitors, who were allowed access to children in the homes.

“In spite of well prepared evidence, many of the abusers have avoided investigation.”

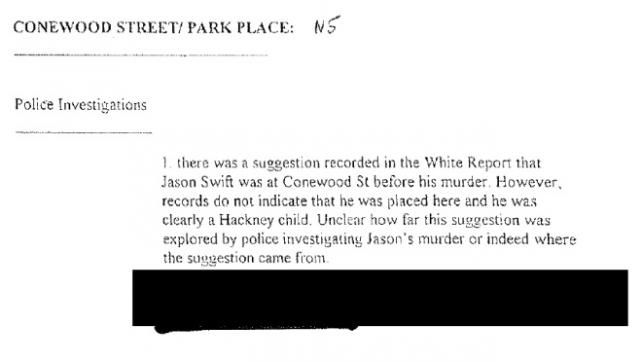

Liz co-wrote 15 reports into the organised child sex abuse network in the borough. However, 14 subsequent inquiries ended with a report in 1995 that found no evidence of such networks. The Morgan QC Review, commissioned by Islington Council, repeated this denial in 2018. Liz says she has testimonies from 60 survivors claiming otherwise.

Liz left Islington disillusioned in 1992, citing as the final straw being asked to place a seven-year-old boy in a foster placement she had reported as abusive.

She went on to work as a child protection manager and trainer in the London Borough of Harrow for 11 years until political changes ended the role.

“From the mid 90s a policy shift took place to destroy the effective protection of children in England and Wales,” she says. “It took place slowly and systematically so that hardly anyone noticed what was happening or realised how sinister the changes were.”

Liz describes this as a shift away from social workers being involved in investigating child abuse to social workers focusing on assessing and supporting families.

She cites the introduction of the 2000 Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need as solidifying this, recalling a training event about managing change that indicated the writing was on the wall: “At this manager’s meeting I could not see my post as child protection manager and trainer anywhere on her redesign chart.”

What followed, says Liz, was an end of social workers and police working jointly in child protection, something she links this to subsequent deaths of children known to services and reviews highlighted failings to share information and “missed opportunities”.

“The Assessment Framework divided the work of police and social workers,” she said. “Social workers were removed from the investigation of child abuse which was seen to be the sole domain of police.

“Instead, social work’s role was restricted to the broad assessment of every child’s needs. Words like ‘risk’, ‘investigation’ ‘protection’ and ‘abuse’ were frowned upon with the intention of seeing the child’s holistic needs. Prevention was pushed at the expense of protecting children from abuse.”

Now in her 70s and emeritus professor of social work at London Metropolitan University, Liz remains an outspoken critic of the child protection system. She blames deregulation and the removal of the child protection register – a database of children subject to child protection plans – for priming the sector for privatisation.

“Lord Laming suggested the abolition of the register which took place in 2008 even though Victoria Climbié might have been protected had she been on it, and Peter Connolly if the emphasis had been to comply with Section 47.

“Privatisation and deregulation were the main goals of government and IT companies needed systems to be minimised and able to be completed by anyone, however unskilled.

“The flow of ideology towards prevention not protection had set in firmly and was propagated by many academics who lost sight of the need for risk assessment and child safety.

“Investigation and intervention became dirty words indicative of a totalitarian state, rather than justifiable, proportionate action to protect children from harm.”

An outlier for many years, Davies’ call for the investigative skills of social work to be strengthened are now more in line with mainstream policy in England and Wales.

The government is planning to rollout specialist multi-agency child protection teams that will include social workers and police as core members in every area. It is also creating a new post of lead child protection practitioner.

A potential cap on profit is among a raft of measures aimed at “rebalancing the market” in children’s social care, with a focus on not-for-profit providers.

Liz welcomes plans to bring back joint working: “Police cannot investigate abuse on their own – child protection investigation required the skills of social workers who know the child and police who understand perpetrators and crime networks.”

But both professions, she said, will need appropriate pre and post qualifying training: “Training must include the skills to analyse the threshold between prevention and protection, and to make decisions about when to escalate and deescalate interventions in order to avoid false positives and false negatives.”

Asked for her message to government, top of her list is to “investigate the invasive takeover of child protection policy and practice by profiteers”.

She would also like to see child protection training made mandatory on police and social work courses and the removal of children’s residential and fostering provision from the private sector.

She called on social workers to stand firm against pressure to practice against their profession’s principles and to “seek allies along this journey”, such as their trade unions and BASW.

Liz urged social workers to “take notice of your intuition and feelings” and use investigative skills and analysis to test them.

For the next generation of practitioners, she offers this advice: “Use the powers you are given by society wisely and responsibly. Power is not always an oppressive concept if it is used to protect the vulnerable.

“Recognise this is a privilege and you have a duty to use this power when needed.

Listen and respond to the views of children and hear what they say through speech and behaviours.

“If a child speaks about abuse, or abuse is reported, then follow child protection guidance and investigate with colleagues from other agencies. This is what being proactive means.”